Film scoring is often one of the final processes in filmmaking, which often takes place during postproduction. After everything is shot and edited, the composer is given a work print of the film and begins to analyze it, deciding what music to write. A work print is an almost complete version of the film, with all the scenes fully edited, without any music. During this process, the composer what music to put over the film, as well as when not to play any music. The silence of a composer can contribute greatly to the emotions of a scene. As Spielberg has said, in regard to his longtime collaborator, John Williams, “Great composers like John know that the power of music also lies in the absence of music” (I would imagine the intensity of the T-Rex scene in Jurassic Park would be dismissed had there been music playing).

What if a film was shot and edited around an already finished score? Of course, this has been done several times in the past. Death in Venice (1971) or Walt Disney’s Fantasia (1940) are examples of works that were made around the music. However, these films, along with several other Silent Era works, used various well-known classical pieces. Some of cinema’s greatest moments include Stanley Kubrick filming around some of music’s greatest compositions. 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) famously uses works by György Ligeti and Richard Strauss, among others, to great effect, with the music adding scale and weight to the films’ atmosphere and themes.

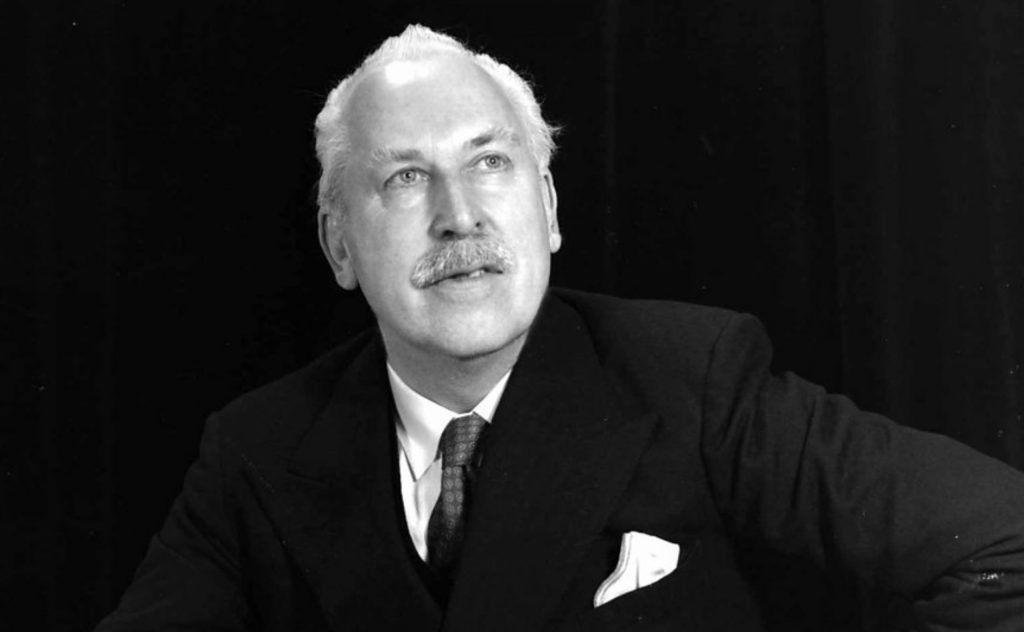

Let’s rewind back to 1934, when author H.G. Wells, who previously never worked on a motion picture, approached the accomplished classical composer Arthur Bliss, who also never worked on a motion picture, to not only score the film adaption of his 1933 novel, The Shape of Things to Come, but to write all the music before production and have the footage match the music. I should also mention the music director, Muir Mathieson, also had no previous experience working on a major motion picture.

The 1936 film, commonly known as H.G. Wells’ Things to Come, is a prophecy of a great war almost eradicating civilization, the rebuilding of society, and the creation of a utopia. The ending of the film takes place in the year 2036. With themes of war, compassion, and societal progress, the music was to encompass these themes and then some. Wells’ idea to want the film to work around the soundtrack was peculiar: He was quoted as saying, “The music is a part of the constructive scheme of the film, and the composer, Mr. Arthur Bliss, was practically a collaborator in its production. . . . This Bliss music is not intended to be tacked on; it is part of the design”.

Bliss had composed several beautiful pieces for orchestras beforehand (his most known work being the lavish A Colour Symphony). His style was brash, bombastic, and proud. Having him do the score to a film that would work around his compositions sounded like a great idea, in theory. Unfortunately, this plan did not come to fruition. Due to scheduling and budget conflicts, Bliss was forced to compose the music after production had wrapped, true to the traditional postproduction workflow. Despite this, the music he created for Wells’ discombobulated mess of a film was exceptional, to say the least. In fact, most critics agree that the soundtrack was the best part of the film (Although, I would argue that director William Cameron Menzies’ production design and special effects would rival the fantastic music. Perhaps now is a good time to tell you that this was Menzies’ first time directing an entire motion picture).

Many tracks from the score became well known outside the film and played by orchestras around the world. Ballet is an innocent piece, portraying the simpler times before the great war. Attack is the destruction of that innocence, with militaristic marching and blazing trumpets. March is overtly British and brilliant., with a fine balance of grace and power. Machines, being my favorite piece in the score, is made up of hope and hard work, playing alongside a brilliantly crafted mortgage sequence. While the song is not a dour song, it is also not entirely cheerful. Machines represents the rebuilding of the world, the rebirth of civilization.

Without hesitation, I can say this is a dazzling soundtrack. I cannot say the same about the film, but that’s for another day. I still recommend watching it, as there are many merits to behold within its web of mishaps. You should not, however, overlook the beautiful score Bliss has written for this film (Please listen to the “Decca Originals” version). It is unfortunate he did not get to score the film beforehand as planned. I’m sure that would have further elevated the film and music. Nevertheless, the music we did receive from his efforts are illustrious. Every song encapsulates the feelings at the time: Inescapable war, paranoia, and ultimately hope for a better future.

Leave a comment